|

| Bombus terricola (left), Bombus pensylvanicus (center) and Bombus auricomus (right), courtesy of the Xerces Society. |

Sadly, as I've delved deeper into bumble bees, I've learned that a number of formerly common Bombus species are in rapid decline due to habitat destruction, pesticides, invasive species, and climate change.

The Xerces Society has a ton of great information about how to protect and conserve bumblebees including this useful publication: Guidelines for Creating and Managing Habitat for America’s Declining Pollinators.

Besides the obvious (stop using pesticides and herbicides) there is some really interesting information about how to create habitat. For instance: most bumblebees nest underground, often in abandoned homes of other animals, including rodents and birds. So by killing mice and other rodents, land owners are indirectly decreasing bumblebee habitat. They also like to overwinter in brushy and unmowed areas, woodpiles, grass clumps, hollow logs, dead trees, and debris piles - which means a little bit of mess is great for the bumblebees, yay!

Xerces Society is conducting a Citizen Science Project to track the status of five declining Bombus species - of course I will be participating, since the idea of a "Citizen Science Project" gets me all fired up and ready to get out my field guides and magnifying glass and Neil deGrasse Tyson T-shirt. One of this summer's goals will be learning to identify different Bombus species. Nerding out with the Bombus in the garden! Because they're big and slow and harmless, I'm hoping they'll be easier to identify than some of the other beneficial insects I've hunted in years past.

More bumblebee information can be found at Bumblebee Watch and you can see some gorgeous bumblebee photos on the USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab's flickr page.

Here are a few Bombus greatest hits photos from my garden over the past few years.

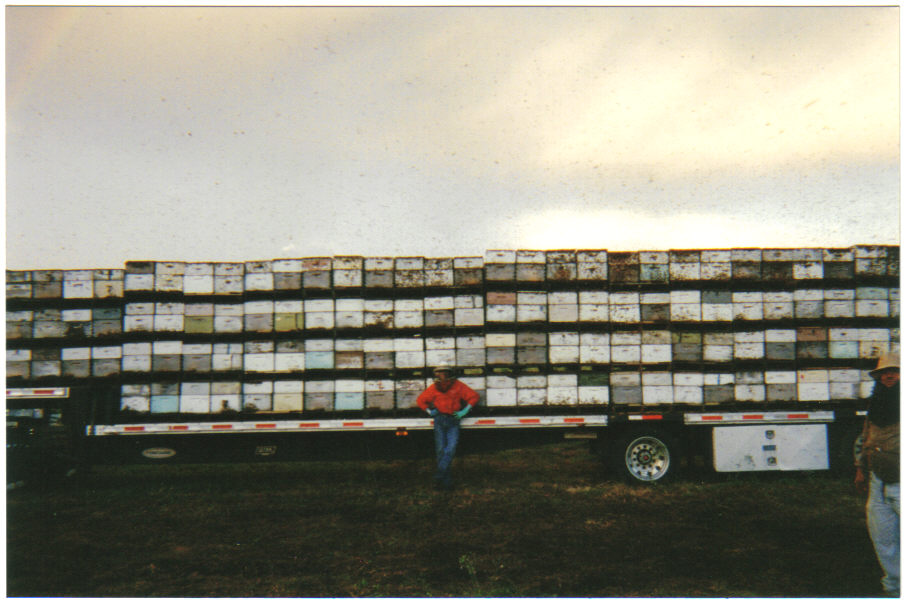

I was astonished to learn that bumble bees are used commercially like honeybees as pollinators for large-scale agribusiness operations. According to one study I found (Plight of the bumble bee: Pathogen spillover from commercial to wild populations, Sheila R. Colla, Michael C. Otterstatter *, Robert J. Gegear, James D. Thomson, Department of Zoology, University of Toronto, available at www.sciencedirect.com): "Since the early 1990’s, private companies have mass-produced and distributed colonies of native bumble bees (Bombus impatiens Cresson in the east and B. occidentalis Greene in the west, although more recently B. impatiens has also been shipped to the west) to large-scale commercial greenhouses for year-round pollination of tomato and sweet pepper. A pollinating force of commercial Bombus can reach 23,000 bees per greenhouse." These large scale commercial bumblebee colonies are apparently one of several factors contributing to native bumblebee decline.

|

| Bombus pensylvanicus female courtesy of DiscoverLife.org |

Besides the obvious (stop using pesticides and herbicides) there is some really interesting information about how to create habitat. For instance: most bumblebees nest underground, often in abandoned homes of other animals, including rodents and birds. So by killing mice and other rodents, land owners are indirectly decreasing bumblebee habitat. They also like to overwinter in brushy and unmowed areas, woodpiles, grass clumps, hollow logs, dead trees, and debris piles - which means a little bit of mess is great for the bumblebees, yay!

|

| Bombus pensylvanicus courtesy of DiscoverLife.org |

More bumblebee information can be found at Bumblebee Watch and you can see some gorgeous bumblebee photos on the USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab's flickr page.

Here are a few Bombus greatest hits photos from my garden over the past few years.